Heidi Fishman

My mother, Ruth “Tutti” Lichtenstern, was born in Cologne, Germany in 1935. In 1936 her father decided to move to Amsterdam to get away from Hitler and the Nazi party. The family was fortunate as her father worked for a Jewish company and the owner of the company decided to move to Amsterdam as well. My grandfather, Heinz Lichtenstern, was able to keep his job with the same company. He was a metal commodities trader and this turned out to be very important in the family’s survival.

My mother’s brother, Robbie, was born in 1938 and was the only member of the family to be a Dutch citizen.

In May 1940 the Nazis invaded the Netherlands and life started to change. The Germans made the changes slowly so that the Dutch wouldn’t revolt. One of my grandfather’s good friends was a man named Egbert de Jong. He was the Rijksminister for Non-Ferrous metal for the Dutch government and after the invasion the Nazis kept him on in the same position, but working for them. He was privy to quite a bit of Nazi planning and he was able to warn my grandfather about some of what would be happening to the Jews. My grandfather gave him an enormous amount of money, 95,000 guiders, and asked Egbert to safeguard it and to use it to help him if he ever had the chance.

Margaret Lichenstern's Dutch ID card with designated letter 'J'

Over the next few years things worsened for the Jews in the Netherlands. They had to carry cards I.D. which were marked with a 'J' and wear the Star of David. The children were segregated into Jewish only schools.

Tutti's class photo - 1942. Jewish school children wearing the mandated Jewish star. Tutti is standing in the third row, 2 places left of the teacher.

In 1942 my mother’s family was moved into one of the Jewish neighborhoods that served as a type of ghetto. It wasn’t fenced in, but the Jews were all in one area and there was a strict curfew. They had to be indoors after 8 pm and the Germans conducted razzias/raids where they would pick a street and round up all the Jews and take them away in trucks. In June all four of my mother’s grandparents, (Louis Spier, Flora Lyon-Spier, Oscar Lichtenstern, Jenny Caro-Lichtenstern) were arrested during a large razzia and sent to Westerbork - a Nazi transit camp in eastern Holland.

The small attic where the family hid - c. 2015

In 1943 my grandfather knew that it was getting more dangerous, so he made arrangements through Egbert to go into hiding. The family went to the attic of a business associate of my grandfather. The couple was a mixed marriage — Leopold Klopfer was Jewish, but his wife, Adele, was not — so they were considered safe from deportations.

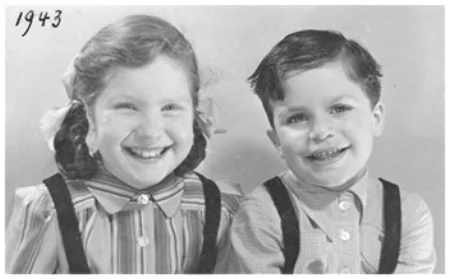

Tutti and Robbie - 1943

After about a month in the attic my grandfather decided he couldn’t take the close quarters and the fear of being caught. His reasoning was that if they were found in the attic they would be killed, but if they followed the rules they had a chance. So the family went back to their apartment in the Jewish neighborhood.

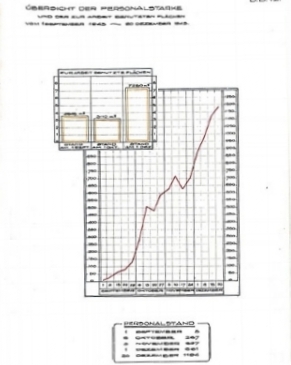

At the end of October 1943 the Germans sent the family to Westerbork, the transit camp in the Netherlands. What happened next was truly astonishing. Egbert de Jong, together with my grandfather and a few other Jewish metal dealers, convinced the commandant of Westerbork to turn the camp into a work camp for sorting scrap metal. As a result of this the Lichtenstern family was released! The Nazis needed my grandfather to be in Amsterdam to help arrange the shipments of scrap.

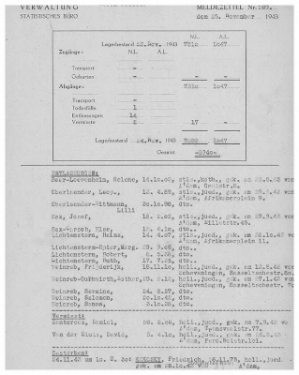

During the last four months of 1943 Westerbork increased the number of Jews separating scrap from 5 to about 1200 workers. This was 1200 Jews not being sent east to the extermination camps.

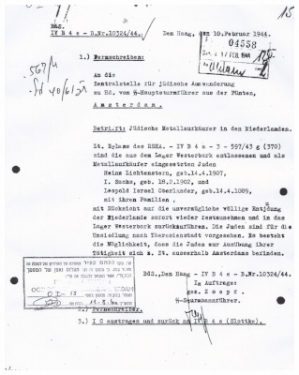

Then in January and February of 1944 Adolf Eichmann and Albert Speer, the Reichsminister for Armaments and Munitions started to argue over what to do with a handful of what they called “metal-Jews,” one of which was my grandfather. Speer’s office wanted to keep them in the Netherlands where they might help the Reich find more metal. Meanwhile Eichmann was working on the Final Solution and wanted them shipped east to the extermination camp. Eichmann won, but compromised. As a result the “metal-Jews” would be arrested, but given privileged status within the camps.

Tutti's doll that her father used to hide money

My mother, uncle, and grandparents were sent back to Westerbork. They were briefly reunited with Tutti’s grandparents, but ten days later all four of her grandparents were sent to Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. The Lichtensterns remained in Westerbork for nine months. During this time my grandfather was often sent to Amsterdam and the Hague to work. On one of his trips he bought my mother a new doll and presented it to her on her ninth birthday in the summer of 1944. He showed her that he had hidden money inside the doll’s head and told her that it was her responsibility to hold on to the doll and guard the money under all circumstances.

Page from a list of transportees from Westerbork to Theresienstadt. The Lichtensterns are #412-415

On September 4, 1944 the family was sent on to Theresienstadt in a cattle car.

While Theresienstadt was considered a “privileged camp,” it was rampant with malnutrition and disease and roughly 33,000 Jews died there from illness and starvation. It was also the last stop before the extermination camps.

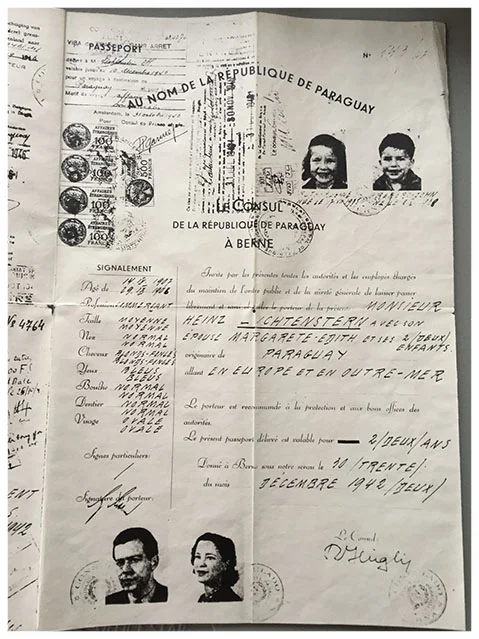

At one point my grandfather was put on a list for the next transport to the “East”. Everyone knew what that meant — death. The money that Heinz had given to Egbert back in the early part of the war now comes into play. Egbert had arranged for a false passport for the family. It was issued by the Paraguayan consulate in Bern Switzerland and said that the family was Paraguayan.

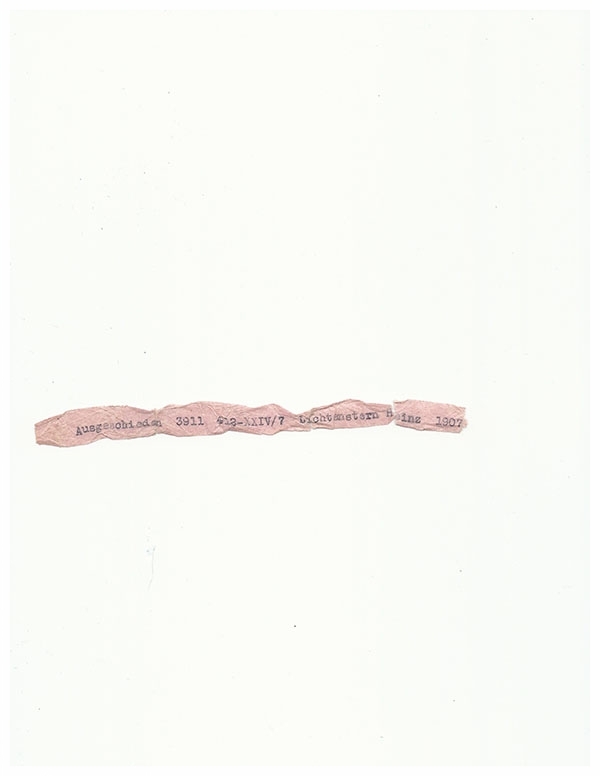

Heinz had that passport all the time since they were in Westerbork. He showed it to someone at the last minute before getting on the transport and he was withdrawn. My grandmother, Margret, saved the little piece of paper that let him off of that transport to certain death.

On May 8, 1945 — on Robbie’s seventh birthday— Theresienstadt was liberated by the Russians. Robbie, Tutti, their parents Heinz and Margret, and their grandparents Oscar and Jenny were all alive at liberation and were able to eventually resettle in Amsterdam. Unfortunately the last transport that went to Auschwitz contained Tutti’s maternal grandparents, Flo and Louis Spier. They were gassed upon arrival. Tutti’s mother, Margret, lost many other family members, including her younger brother Franz Robert Spier and his wife Justine Bendien-Spier, as well as many aunts, uncles and cousins.

Oscar and Jenny lived in Amsterdam until their deaths in 1954 and 1969, respectively. Heinz and Margret moved several times after the war. The family lived for significant portions of time in Amsterdam, Rio de Janeiro, and New York. Eventually my grandparents settled in Luzerne, Switzerland. Robbie moved to London where he married and had two children and two grandchildren. He passed away in 1984. My mother, Tutti, met my father while on vacation in Nantucket and settled in Connecticut. She has three children and seven grandchildren.

My mother has spoken to thousands of school children around New England about her experiences during the Holocaust. I have written a book, Tutti’s Promise, which tells the story in detail and is intended as a legacy to continue the story even after Tutti is no longer able to tell it herself.

Tutti - center - and husband. Her three children, their spouses and seven grandchildren.