Tom Glaser

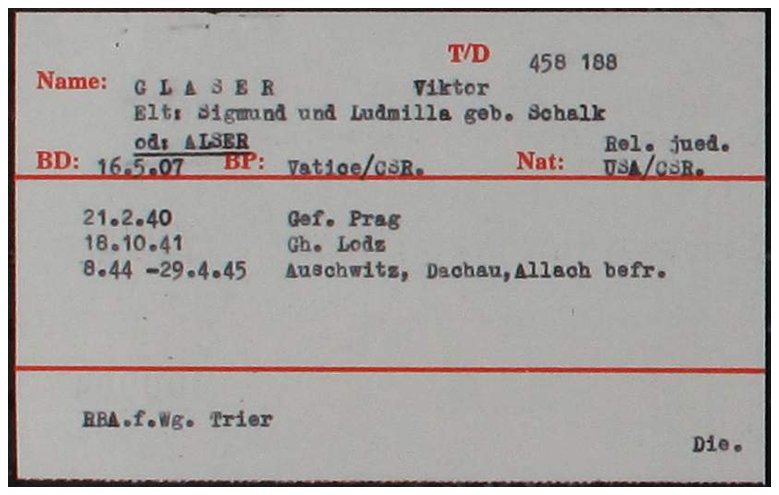

My father, Viktor Glaser, was born in Votice, Czechoslovakia, a small town approximately 40 miles south of Prague, on May 16, 1907. My mother, Theresie (known as “Daisy”), was born in Vienna, Austria, on April 3, 1921. As the dark cloud of Nazism descended on central Europe, a cousin urged my father to flee, but he would not leave without his parents. His parents would not leave because they were old, spoke only Czech, and couldn’t imagine leaving everything behind, including their home and business, which was buying and selling animal skins, feathers and down.

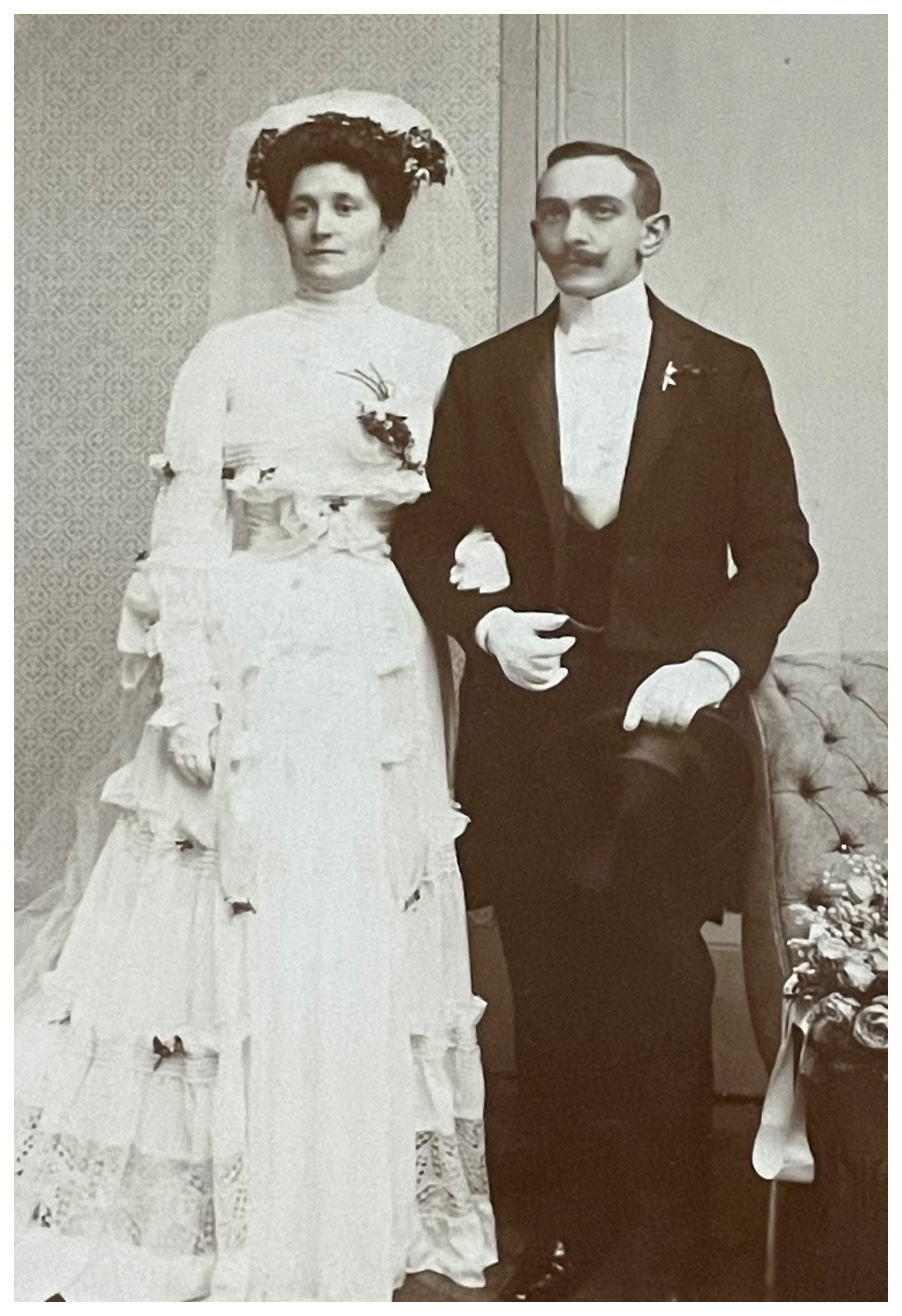

The Germans first occupied the Sudetenland, a province in northern Czechoslovakia bordering Germany in 1938, and the rest of Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939. A month later my parents got married, thinking that marriage might save them.

My father, not knowing what was going to happen, began smuggling his own and other people's money and jewels out of the country on the underside of trains. Someone snitched, and he spent nine months in a Gestapo jail, subject to frequent beatings. He emerged only after his family bribed the authorities. During his incarceration, the Nazi’s appropriated his parents’ apartment and business, and my parent’s apartment. Afterwards, all Jews were forced to wear “the Yellow Star” and could not go to cafes, movies, or other places of entertainment.

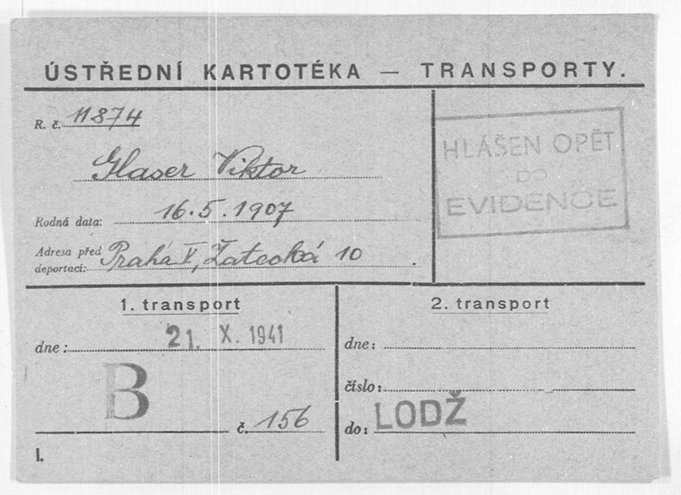

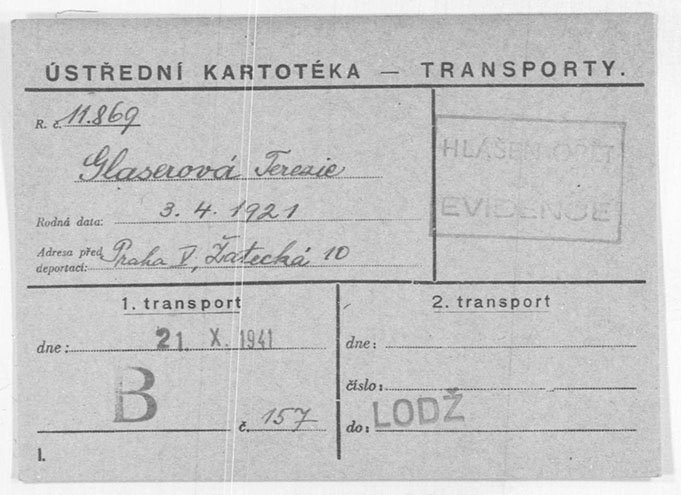

My grandparents and my mother’s brother, were forced to leave Prague on the second of five transports, and my parents joined them voluntarily for what they hoped would be mutual protection. Each transport contained 1000 Jews. The rumor was that they were headed west; the fear was they were headed east. On October 21, 1941 the transport headed north, to Dresden, Germany, then east, to Lodz, Poland, where 1,000 people were then jammed into a single building, 25 per room, “like sardines, but humans.” Eventually, 160,000 Jewish “visitors” crammed into the Lodz Ghetto. The daily food ration was 12 ounces of bread, and soup made from rotten vegetables, “not fit for pigs”, as my father described. The young men had to pull horse carts containing food into the ghetto and feces out of the ghetto. My father got a job in an office, working 17 hours a day, 7 days a week, and caught pneumonia. He left the hospital in such a weakened state that the doctors didn’t think he would survive.

In the spring of 1942, more Jews, from western countries, entered the ghetto; and current Jews were forced to leave. My mother’s parents and brother, and all other relatives and many friends were forced to leave. None of them ever returned or were heard from again. They were brought to eastern Poland, where many were forced into open graves and shot dead. Jews from surrounding areas arrived, as many as 200 people in a sealed cattle car, many dead from asphyxiation. Of course, disease was rampant, and my father's father died on August 18, 1942. Right after, my father developed jaundice; he weighed less than 110 pounds; my mother developed typhus, and her fever reached 104 degrees for 6 weeks; neither of which boded well for the “selections'' that would determine who would live and who would die that were starting to take place. On Tuesday, September 8, 1942, the residents of my parent’s building were forced outside, and the Germans selected my grandmother to die. Families were torn apart, and babies were ripped out of their mother’s hands and thrown onto trucks, one on top of another.

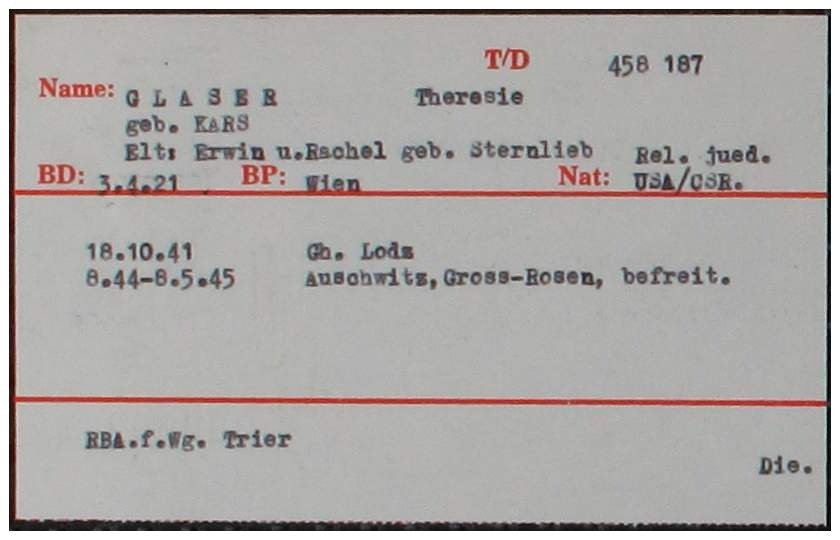

By 1944 the Russians were coming from the east, and the Germans moved the denizens of the Lodz Ghetto south, to Auschwitz, 60 to 90 people per cattle car. Upon arrival, my mother was sent to the “fortunate side”; those on the “unfortunate side” were never seen again. My father suddenly found himself face-to-face with the notorious Doctor Josef Mengele, whose finger movements indicated life or death. The living were whipped, forced to undress, shaved, bathed, given old clothes, beaten until bloody, and forced into crowded cell blocks. There were latrines, but no toilet paper! Day and night, without pause, flames came out of the chimneys of the gas chambers.

Life settled into routine. Little food and lots of painful, bloody roll calls. The guards, though, were unpredictable as to whom they would help and whom they would kill. My father, now wearing the infamous black and white striped prison uniform, joined 600 other prisoners heading for Bavaria, Germany. The first night of a three-day journey, my father ate his entire ration of bread, consisting of two slices of bread, two slices of salami, and margarine.

From Auschwitz my mother went to a camp in Mezimesti u Broumova called Grosse-Rosen on the Czech-German border. She worked in a factory near the camp.

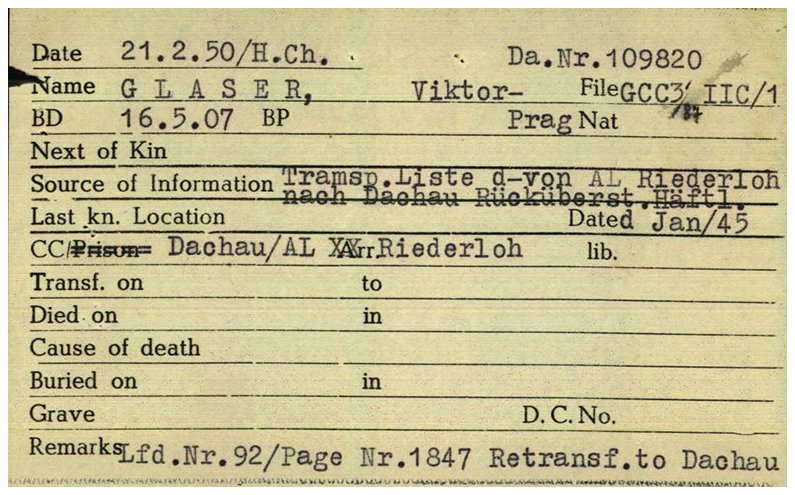

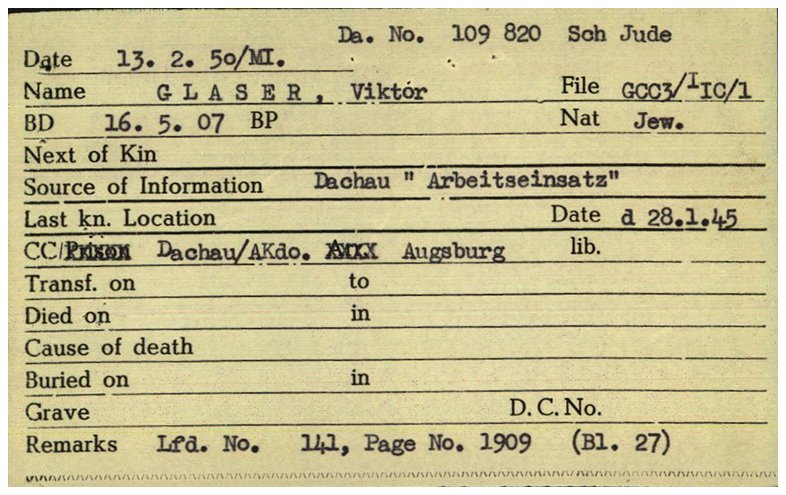

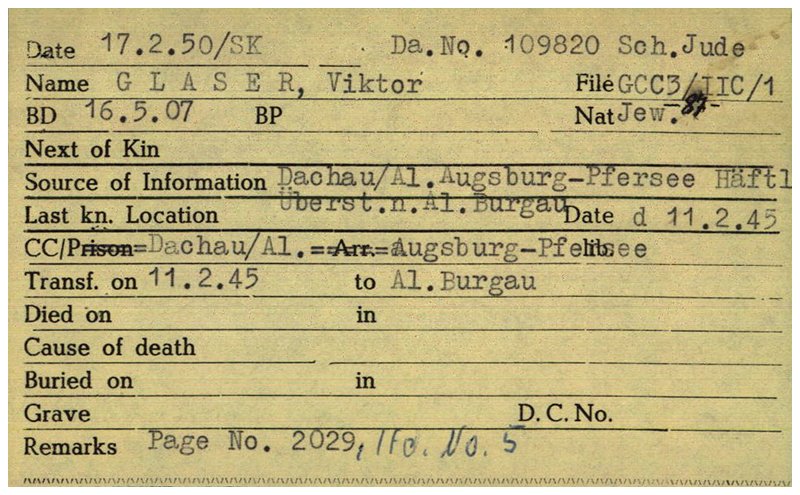

In Bavaria, the prisoners were forced to march 10 miles a day and to labor hard. Not surprisingly, every day 10-20 prisoners perished. New prisoners arrived, and soon hundreds of lice covered everyone. In the winter of 1944-45, the work got harder, and the weather got colder. The Germans beat many prisoners to death, removing the gold from their teeth before tossing them into mass graves that my father helped dig. He worked from 3:00 AM until 8:00 PM. On a precious few occasions, an SS officer would tell my father where an extra bowl of soup was or where he could get an extra piece of bread. It wasn’t very often. Eventually, the Germans moved my father from Bavaria to Dachau to Augsburg to Horgau to Burgau to Tuerkheim, back to Dachau, and eventually to Allach. The journey from Tuerkheim to Dachau started on April 24, 1945, with the allies fast approaching. The Germans force-marched the prisoners 53 miles, with much rain falling and many people dying along the way from exhaustion and/or being beaten. Between April 28-29 the SS left and the Wehrmacht [regular army] arrived. That night my father was caught in the middle of a heavy artillery bombardment; the explosions killed or injured many prisoners right next to him.

On April 30, 1945, the Americans liberated the camp. When soldiers came into the barracks, many prisoners, unfortunately, could not control themselves. They ate so much of the food that the Americans innocently gave them that they died because their empty stomachs could not handle the change.

They escorted my father to Prague, where he arrived on May 24th. My mother had also survived the war, having an easier time working in the factory. My father later described their reunion as “indescribably happy.” Less happy was the news that out of 5,000 Prague Jews in Lodz, only 135 ever returned.

Immigration Documents for my parents and brother to the USA March 2,1949

My parents received back some of their property that the Germans had confiscated, and they moved on with their lives. My parents fled Prague in 1948 when there was a takeover by the Czech communist party. They emigrated to America and settled in a suburb of New York on Long Island, where they raised my brother, George, who was born in Prague on January 5, 1947 and me. I am the first one in the family born in the US.

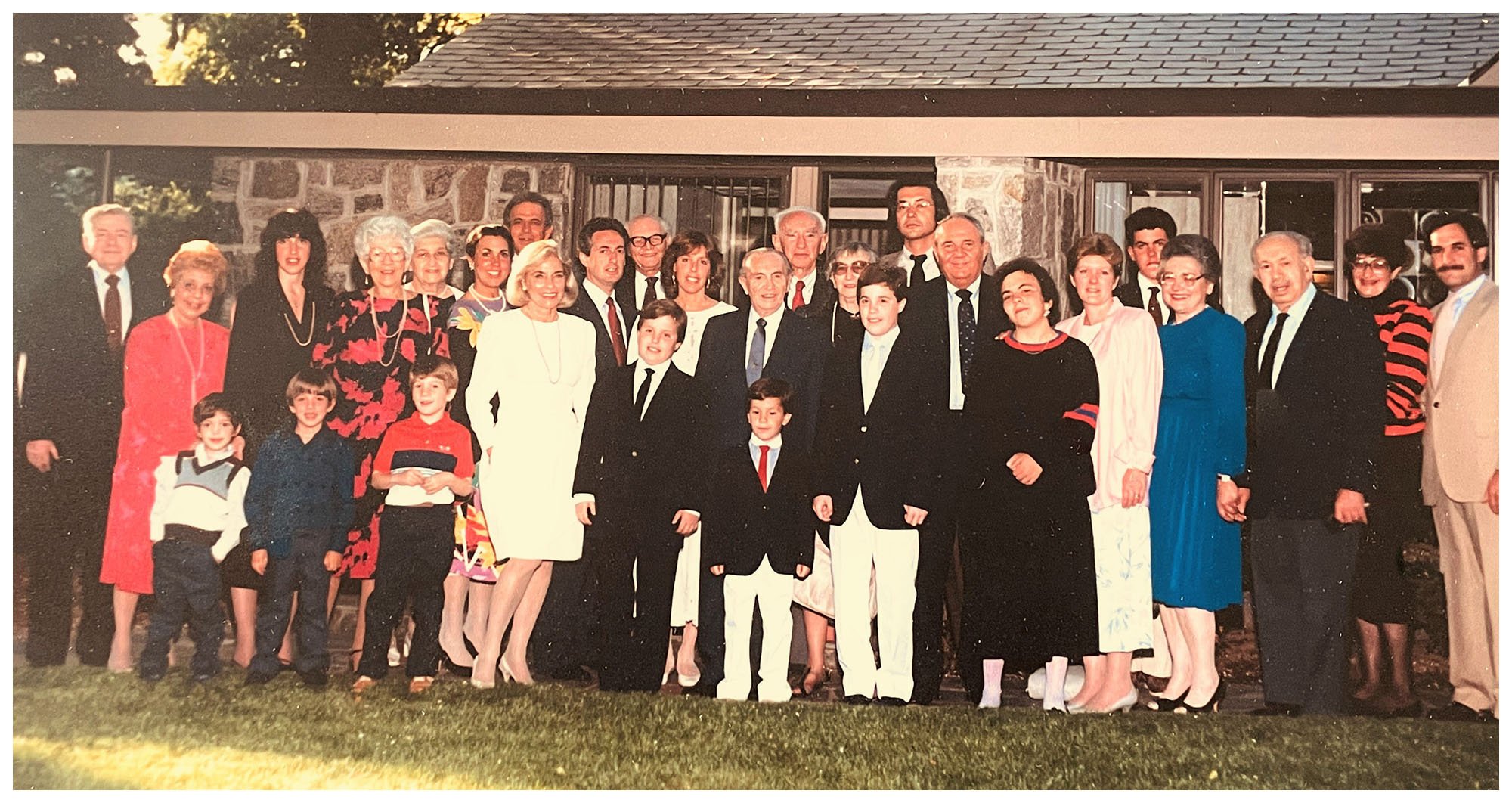

My father was able to continue doing what he knew best, buying and selling feathers and down. We had a nice life. In the winter we went skiing, and in the summer we did a lot of boating and waterskiing. My brother and I were quite good at ski racing, and that is what got me to Vermont. I went to UVM to be on the ski team. Jill and I got married in 1970 and stayed in Vermont after I graduated. We raised 3 boys, have 3 grandchildren, and we live on beautiful Lake Champlain in Shelburne.

Daisy approximately 30 years old, - Roslyn Heights, NY - 1951

I am grateful that my parents met and became lifelong best friends with another surviving couple, Karel and Jirina Krasa. Only 19 couples survived out of the 5000 that were taken from Prague. They had a daughter Barbara who is like a sister to me. Growing up we were like family.

My mother died on January 22, 1969 at the age of 48, when I was only 19, a freshman at UVM. She survived the holocaust, but nevertheless was a casualty of it.

Viktor and Daisy with brother George, and me: 1964

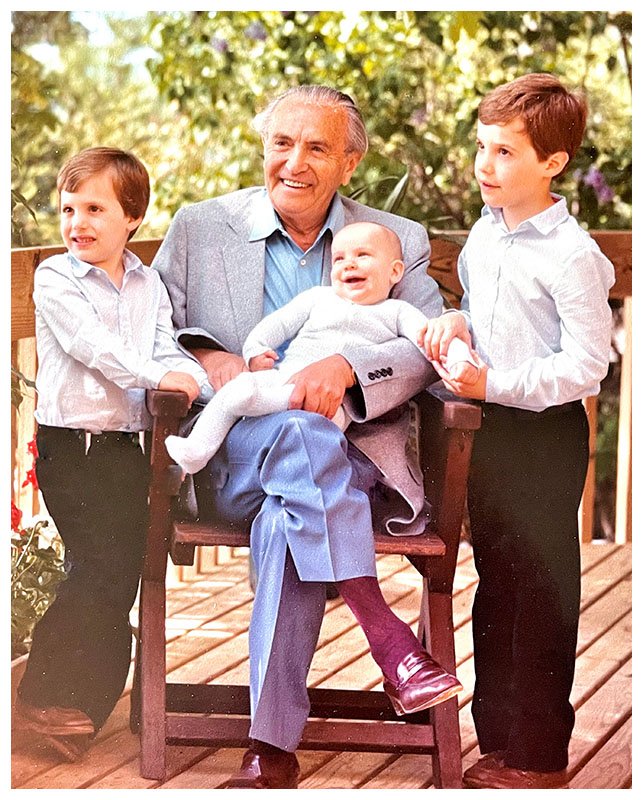

My father died of Alzheimer’s disease on October 6, 2000, at the age of 93.

Hitler killed far too many, but thankfully my parents survived so the Glaser Spirit lives on.